An animal that lived before the dinosaurs looked like a plump lizard with a very small head and had a semi-aquatic lifestyle similar to that of a hippopotamus, according to fossils recently unearthed in France.

The amphibian animal, which represents a previously unknown genus and species of a mammalian ancestor, was about 4 meters (12 feet) long, the researchers reported in the journal’s October issue. paleovertebrate, published online in July. They named the new species Lalieudorhynchus gandi; lived about 265 million years ago in the pangea supercontinent, just before the age of the dinosaurs.

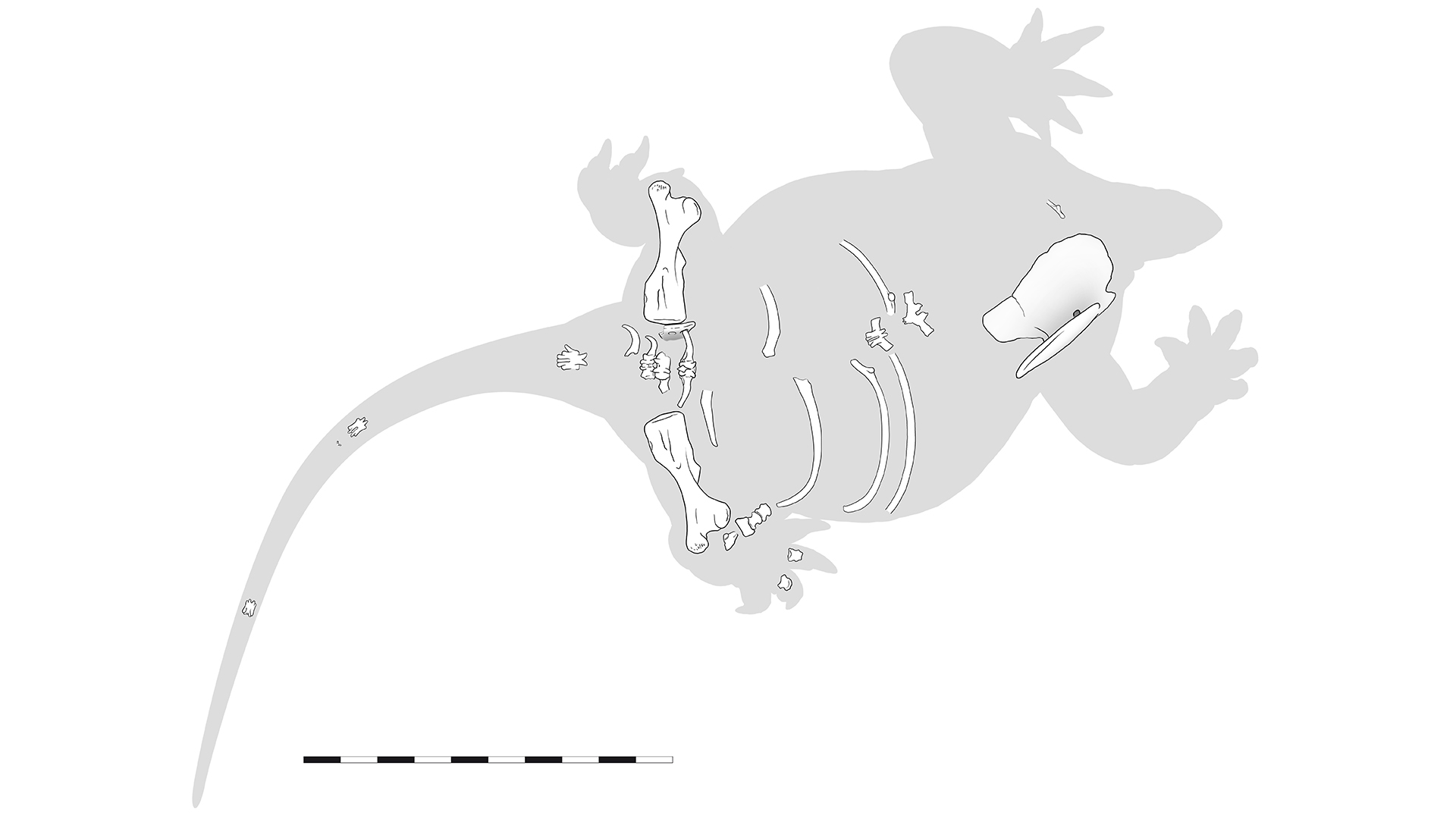

Fossils of the unusual animal were first discovered in 2001 in the Lodève Basin in southern France by study co-author and paleontologist Jörg Schneider, a professor in the Department of Paleontology and Stratigraphy at the University of Freiberg in Germany, and doctoral candidate Frank Körner. . They found two large ribs, each 60 centimeters (24 in) long, in a rocky stream bed. During subsequent visits to the site, Körner found additional bones of the mysterious animal: a 14-inch (35 cm) long femur and a 20-inch (50 cm) long shoulder blade.

Their analysis has been 20 years in the making, largely because the fossils were encased in concrete-hard sandstone and their preparation took years to complete, the researchers reported in the study.

From this partial but well-preserved skeleton, paleontologists deduced that the primitive creature was a type of caseid, an extinct group of fossil reptiles that possessed mammalian features and are thought to be the ancestors of mammals, in the genus Lalieudorhynchus. Described in the press release as a “chubby lizard” and a 3.5-meter-long “lump of meat,” the creature lived during the Permian, a period that began about 299 million years ago and ended about 252 million years ago. million years with the beginning of the Triassic period (and the rise of the dinosaurs).

Related: The ancient hippo-sized reptile was a fast and ferocious killing machine

Fossil rib, shoulder blade, and femur of Lalieudorhynchus. (Image credit: Ralf Werneburg) (opens in a new tab)

Caseids were primarily herbivores, perhaps some of the earliest herbivores in evolutionary history. They they had small heads and barrel-shaped bodies they contained large digestive tracts for breaking down plants, and despite their reptilian appearance, caseids were ancestors of mammals. .

“The very diverse group of mammalian ancestors was the dominant group before the ages of the dinosaurs,” Frederik Spindler, a co-author of the study and scientific director of the Dinosaur Museum Altmühltal in Denkendorf, Germany, told Live Science. When Spindler examined the newly discovered fossils, he concluded that they belonged to a new species. There have been fewer than 20 caseid species identified in the fossil record to date; most came from the United States and Russia, but some have recently been found in southern Europe, Spindler said.

Skeletal remains of Lalieudorhynchus discovered. (Image credit: Frederik Spindler) (opens in a new tab)

However, L. gandi could be a particularly advanced caseid species, unlike anything seen before, Spindler added. “New genera are diagnosed by detailed anatomical comparisons,” and the analysis of L. gandi was conducted by study lead author Ralf Werneburg, director of the Natural History Museum at Bertholdsburg Castle in Schleusingen, Germany, Spindler said. Werneburg identified five unique features “that are not known from any other caseids, and 20 more that make up a unique combination within this family,” Spindler explained.

This newly identified creature is not the so-called missing link in any evolutionary lineage of the mammalian family tree, but its status as one of the youngest caseids found so far may be significant for understanding mammals. evolution. “It adds to the known diversity of large caseids, marking them out as a very important herbivorous group,” Spindler said. Furthermore, L. gandi could be the pinnacle of evolution of all caseids before they went extinct, meaning the species had the most advanced features of the group, Spindler said.

The structure of the L. gandi bones, which were spongy and flexible when viewed under a microscope, hinted to the study authors that the ancient caseid might have led a semi-aquatic lifestyle, much like modern ones. hippos. In life, L. gandi likely weighed hundreds of pounds, and all that body weight may have required additional support from immersion in water, according to the study.

However, L. gandi is not a relative of hippos, and any similarity to modern hippos is in the ancient animal’s habits and not its anatomy, Spindler said.

“Spongy bones may imply a diving lifestyle in some extinct marine amphibians and reptiles,” Spindler said. By comparison, most mammals, including hippos, have denser bone tissue. “Our new caseid would swim better, whereas hippos walk closer to the ground,” Spindler said.

“A low-browsing, semi-aquatic lifestyle is what large caseids share with hippos, if we’re right,” Spindler said. “Lalieudorhynchus gandi could be said to have ‘invented’ a niche that hippos later repeated.”

Originally published on Live Science.

Source: www.livescience.com