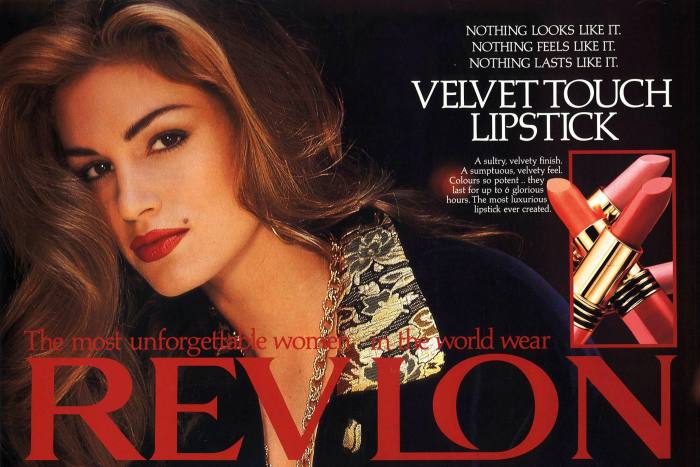

In Revlon’s heyday in the 1980s, supermodels Cindy Crawford and Claudia Schiffer appeared in television and magazine ads promising to make women “unforgettable” with the brand’s bright red lipsticks.

Today, consumers search for cosmetics on social media and a flood of independent brands spearheaded by celebrities like singer Rihanna and influencer Kylie Jenner have pushed the likes of Revlon to the side. Saddled with high debts, the 90-year-old US group, majority-owned by billionaire Ron Perelman, filed for bankruptcy protection last week.

The high-profile victim shows how competitive and fast-paced the beauty industry has become, requiring heavy investment in digital marketing and product innovation to prevent brands from fading and becoming irrelevant. Unlike other staples like food or home products, where brands can survive decades with minimal tweaks, consumers’ desires for beauty evolve rapidly, often under the influence of culture, fashion and art.

“Indie brands are constantly taking risks and starting trends,” said Stephanie Wissink, an analyst at Jefferies. “It’s as if the big established beauty companies are like a tortoise, not competing against a hare, but against hundreds of them.”

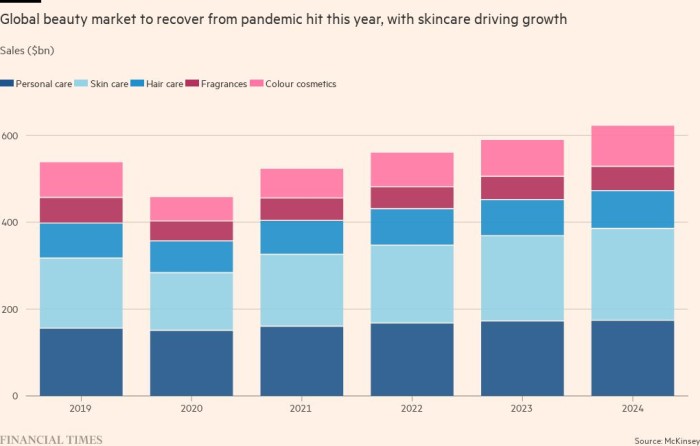

You are viewing a snapshot of an interactive chart. This is most likely because you are offline or JavaScript is disabled in your browser.

Industry leaders L’Oréal, Estée Lauder and Shiseido have learned to thrive in this new landscape by leveraging their global reach and scientific insights, and acquiring the most promising independent brands to stay relevant.

But the likes of Revlon and Coty have struggled because their cosmetics are more for the mass market and lacked scale in the fastest-growing category and market: skin care and China. Both have been constrained by debts racked up from acquisitions, though Coty has made progress on repayment, so analysts say it is unlikely to suffer Revlon’s fate.

The pandemic pushed less agile businesses even further, as lockdowns and mask wearing hit demand for beauty products and sent more consumers online. Supply chains for everything from plastic to pigments have become tangled, another advantage for larger companies that have more leverage with suppliers.

Global makeup sales have not recovered to their 2019 levels, although some categories such as skincare and luxury fragrances have, according to data from McKinsey.

The strongest players, L’Oréal and Estée Lauder, have already surpassed their pre-pandemic sales, helped by their large presence in the burgeoning Chinese market and their strength in skincare with brands like Lancôme and La Mer. L’Oréal has forecast that its revenue growth will outpace the 4-5 percent expansion of the global beauty market this year.

In contrast, sales at Revlon, Coty and Shiseido are still languishing at pre-pandemic levels.

Even winners in the beauty industry have had a rough patch in the stock market this year, as a combination of China’s Covid-19 restrictions and fears of a global recession alarm investors. Estée Lauder is down 30 percent, L’Oréal is down 22 percent and Shiseido is down 18 percent, all underperforming the Dow Jones Industrial Average and global consumer staples indices. Coty is down 30 percent this year and Revlon is down 38 percent.

You are viewing a snapshot of an interactive chart. This is most likely because you are offline or JavaScript is disabled in your browser.

Although China has proven to be a boon over the past decade for some beauty companies, Beijing’s zero-Covid policy has curbed its attraction this year.

Estée Lauder, in particular, has been hit hard by recent shutdowns in China, prompting a profit warning in May. China accounts for around a third of its sales and its main distribution center is in Shanghai, the heart of the recent Covid outbreak, which prevents it from supplying the rest of the country.

Given China’s role as the second-largest cosmetics market after the US, Jefferies’ Wissink said China will continue to control the sector unless authorities back away from their strict Covid-19 policy.

But in Paris, a destination for Chinese tourists when travel was easier, there were few signs of slowing down at the city’s Bon Marché department store this week, where independent brands like Charlotte Tilbury compete for attention alongside mainstays Dior and Chanel. .

Revlon ads promised to make women ‘unforgettable’ © Retro AdArchives/Alamy

A sales clerk who declined to be identified said he had been busy since international tourists returned and wedding season was in full swing. “People want to pamper themselves, so they’ve been buying beauty products that make them feel good,” the person said.

Elena Boulard said she had come to the store for a new lipstick and bronzer because she planned to go to the office more this summer after a long period of working from home. “I haven’t bought makeup in a long time and there are so many new things.”

High-end beauty products have fared better coming out of the pandemic than cheaper brands. In the US, the “prestige beauty” market, which includes products sold through specialists like Ulta and department stores, grew strongly last year to $22 billion, or 7 percent above 2019 levels, according to market researcher NPD.

Luxury fragrances, including new brands offering custom blends for an individual, have also enjoyed a renaissance. “Consumers are buying a $300 bottle of perfume instead of an $80 bottle,” said NPD’s Larissa Jensen.

For Revlon, the nascent recovery has come too late. But its troubles go back much further: Sales have been stagnant for much of the past two decades, except for a spike in 2016 when Revlon bought Elizabeth Arden, and it has posted losses for the past six years.

Analysts said Revlon’s brands failed to keep up with changing consumer tastes, which began to emphasize self-expression and embracing flaws over unattainable beauty standards. Revlon’s weakness in skincare also meant it didn’t benefit from the rise of that category.

An extended balance sheet left the group unable to acquire independent brands to update its product lines. Following its filing in bankruptcy court, the company will continue to operate while working out a payment plan for creditors.

Customers try out skin care products at a Chinese shopping mall © Imagine China via Reuters

Customers try out skin care products at a Chinese shopping mall © Imagine China via Reuters

The way indie beauty brands often emerge from unexpected places underscores the scale of the challenges Revlon faced with flat feet.

Take Half Magic, a brand started in May by Doniella Davy, a makeup artist who rose to fame creating “emotional and glamorous” looks for actresses on the hit US television teen drama Euphoria. On TikTok, the hashtag #EuphoriaMakeUp, where people post videos of themselves donning brightly colored eyeshadow, glitter and neon face gems inspired by the show, has amassed 2.1 billion views.

While Half Magic may fizzle out, it’s emblematic of how new brands and trends flourish on social media. To monitor the changes, big beauty companies have increased their spending on digital marketing, both to advertise their brands and to take advantage of trends when they emerge.

“If you want to run a successful cosmetics business today, you have to pay an army of 20-somethings to be on TikTok and Instagram all day to monitor trends and engage with people about their brands,” said Iain Simpson, an analyst at Barclays. “It’s not a business that can be run efficiently and with a lot of debt.”

Recommended

Coty CEO Sue Y Nabi said in an interview that the group had “made a lot of progress” in using social media to revamp its storied mass-market brands, which include CoverGirl and Max Factor. “Staying relevant is the most important thing,” she said, including tapping into consumers’ desire for “clean beauty” products that eliminate harsh chemicals or using TikTok to appeal to Gen Z consumers.

An example of Coty trying to update older names was the recent launch of a mascara under its Rimmel brand. He enlisted a UK TikTok influencer, Olivia Neill, to help design and promote the product called Thrill Seeker.

“It’s the first time we’ve done something like this,” Nabi said. “Companies like ours have learned to create viral products just like independent brands do.”

Source: www.ft.com