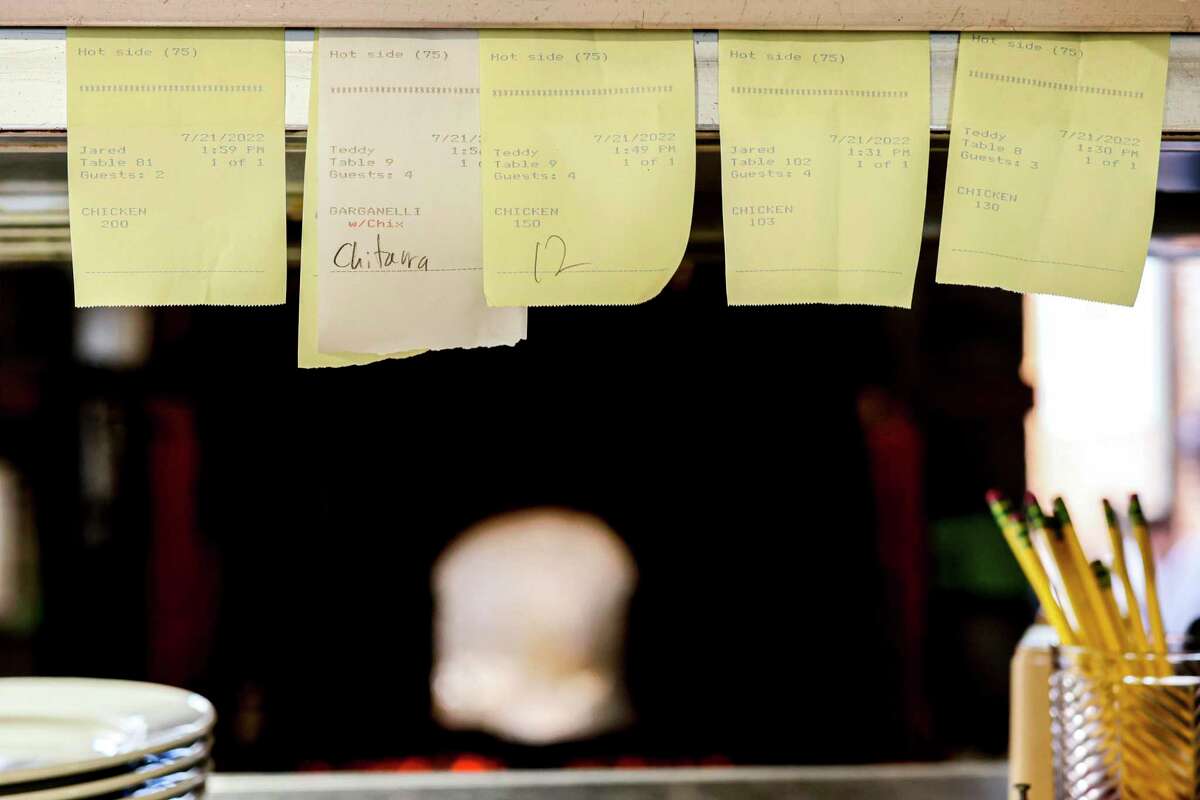

Many hands touch Zuni Cafe’s famous rotisserie chicken before it reaches a diner’s table: the cook shredding the birds, the sous-chef keeping an eye on them as they brown in the rustic wood-fired oven, the waiter bringing the Large dishes in the dining room.

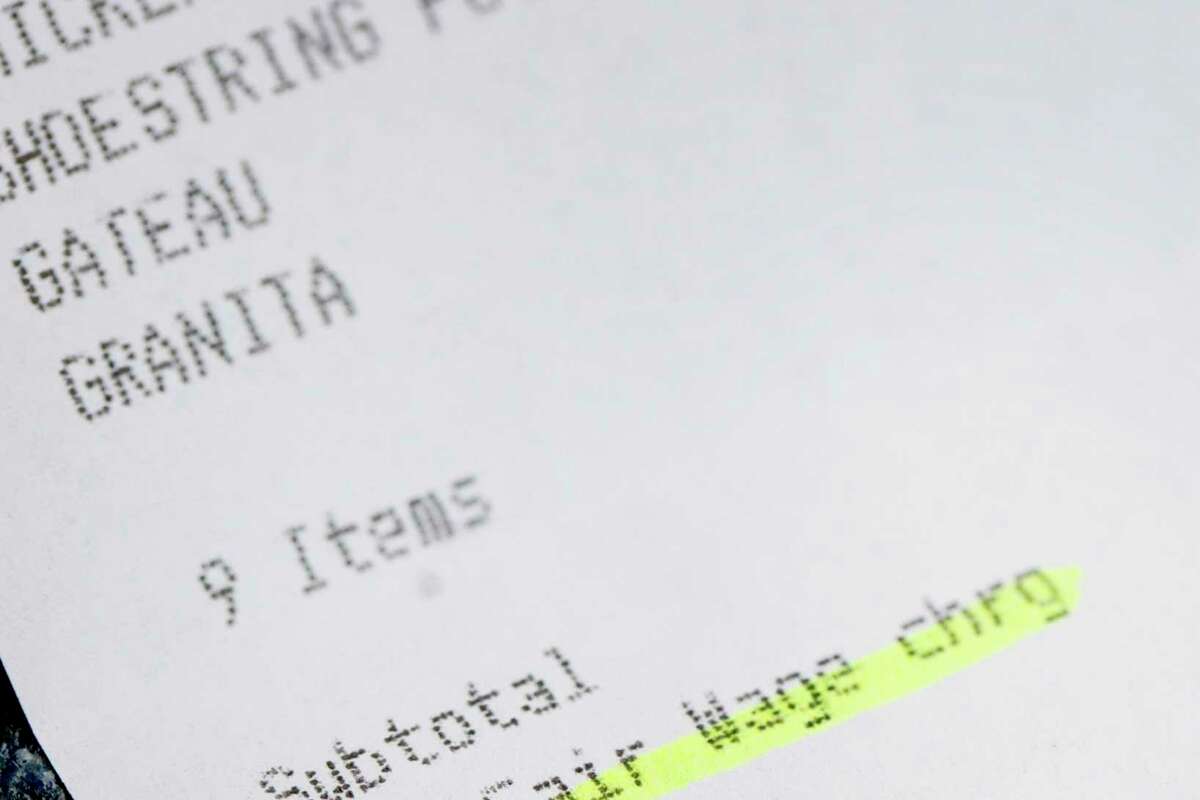

When the legendary San Francisco restaurant made headlines last year with its decision to replace tips with an automatic 20% “fair wage” surcharge, the goal was to raise the wages of the lowest-paid workers in the kitchen, a recognition that every employee who helps make Zuni chicken deserves to earn enough to live in the Bay Area. While hailed by many as an upbeat change in the industry, the move has sparked tensions within the restaurant.

Zuni servers, while supportive of the spirit behind the new model — balancing historic inequalities between kitchen and front-desk staff — now say they are struggling to make ends meet without taking home more tips. His frustration has reached the point of discussing a strike or unionizing to put pressure on Zuni. Due to the server pushback, the restaurant is discussing potential changes to the model, owner Gilbert Pilgram said. But going back to tipping is “not on the table,” he said.

The bill at Zuni Cafe includes a 25% fair wage charge, Thursday, July 21, 2022, in San Francisco, California.

Santiago Mejía / The Chronicle / The Chronicle

Zuni Cafe, Thursday, July 21, 2022, in San Francisco, California.

Santiago Mejía / The Chronicle

Pictured above: Kate Sachen serving customers at Zuni Cafe. Above: Bills at Zuni Cafe (left) come with a 25% surcharge: the 20% “fair wage” rate plus the 5% San Francisco health mandate fee. Diners enjoy a meal in the restaurant (right). Santiago Mejía / The Chronicle

“No restaurateur is interested in having a system that keeps any part of the restaurant unhappy,” Pilgram said. “That is a recipe for disaster.”

The tipping debate is not new to the industry. Any change to the typical system usually creates controversy between servers, who fear lower wages, and clients, who may feel robbed of their perceived right to reward staff. Some Bay Area restaurants have shown it can be an enduring practice, like Zazie in Cole Valley and Berkeley’s Chez Panisse institution. Meanwhile, other prominent companies have ended their tipless experiments, such as Danny Meyer’s Union Square Hospitality Group in New York City.

The pandemic brought a new urgency to the problem when it plunged restaurants into unprecedented staffing shortages. Many owners took the opportunity to reinvent their compensation structures. Tipping, which has been shown to create pay inequality and encourage racism and sexism, was re-examined on a larger scale.

This is the latest in a four-part series that examines how Bay Area restaurants are working to transform the industry, from eliminating tips and raising wages to establishing worker ownership. Read the first three stories about Good Good Culture Club, Che Fico and Understory on SFChronicle.com.

see more

Given Zuni’s stature in the industry, many restaurateurs have been closely watching its progress amid what feels like a tipping point for fairness and change in restaurants. The friction serves as a reminder that it is not that easy to achieve.

“I agree that the back-of-house deserves more money. We waiters are suffering a lot,” said waitress Kate Sachen. “A lot of us wish it would just go back to the old system.”

The success of the Zuni model depends on who you ask. Thanks to the surcharge, hourly kitchen staff saw their salary increase between 35% and 58%. Turnover is low in the kitchen despite continued labor shortages, executive chef Nate Norris said. Fewer cooks and dishwashers have second jobs, he said.

Chef and dishwasher Carlos Garcia, who has worked at Zuni since 1989 and prepares all the chickens, has benefited directly. The 63-year-old Mexico City native can finally start saving for his retirement.

Server Richard Wade talks to customers at Zuni Cafe. It has long been one of Wade’s favorite restaurants, but now he feels conflicted about working there.

Santiago Mejia/The Chronicle

“I’m getting old and I need to take care of myself,” Garcia said.

Norris, who serves as a spokesperson for Zuni, has been working hard to break the entrenched belief that the kitchen and dining room are separate entities and that tips should be distributed as such. But servers still “see that money as theirs,” he said, “and not only earned it, but exclusively earned it.”

When Pride Weekend brought a throng of customers to Zuni in late June, waiter Richard Wade worked long shifts that took a toll on his body, he said. They didn’t end up with the usual reward of cash tips in his pocket.

“Normally, if you work with those kinds of people, you’d be making a lot of money,” he said. “In this tip system, I made exactly the same amount as if I had sold $800 instead of $3,000.”

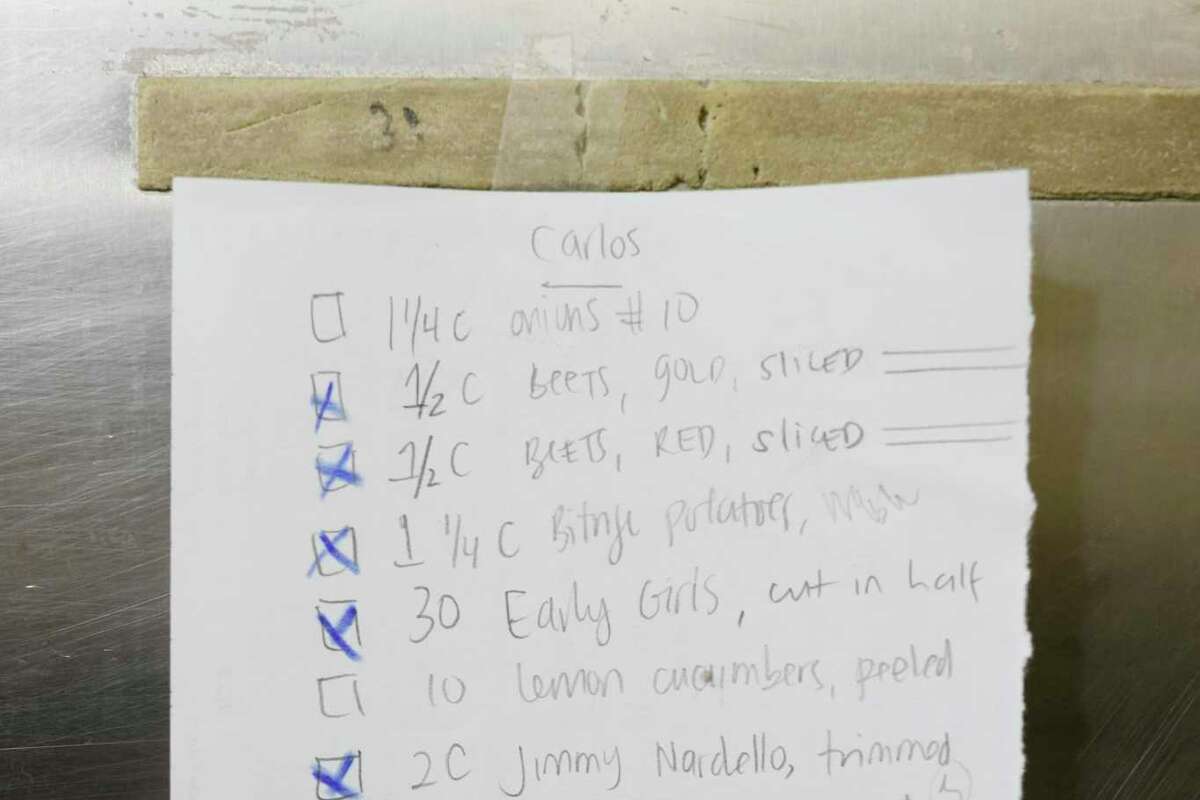

Carlos Garcia stocks meat at Zuni Cafe, Thursday, July 21, 2022, in San Francisco, Calif.

Santiago Mejía / The Chronicle

Carlos Garcia keeps a to-do list for work at Zuni Cafe, Thursday, July 21, 2022, in San Francisco, California.

Santiago Mejía / The Chronicle

Chef and dishwasher Carlos García carries a tray of meat (left). Thanks to Zuni’s new model, he can finally save for his retirement. He keeps a to-do list (right) of daily tasks. Santiago Mejía / The Chronicle

Sachen has relied on tips as part of his income for more than a decade at restaurants in San Francisco, San Luis Obispo and Minneapolis. He loves working at Zuni, but has salary problems. At $32 an hour, plus additional work as a voice coach, she said, it’s challenging to afford living in San Francisco, the exact problem the model was meant to solve for the kitchen staff.

Wade, Sachen and other servers take particular issue with how Zuni distributes tips charged to credit cards, with 36% going to the server and the rest to the servers, waiters and administrative staff. Whether a server shares cash tips with other staff is at their discretion. (Zuni also maintained an optional tip line, meaning diners can choose to leave a tip in addition to the 20% cover charge.)

“It seems to me like a car dealer’s commission, and then the car dealer only gets 36% of the commission and the rest goes to the manufacturer,” Sachen said.

Most diners bear the service charge, plus the occasional mix-up or shock of etiquette, employees said. Some ask why Zuni doesn’t raise prices. Restaurateurs are often wary that raises will turn off diners, and the point of the fair wage surcharge is also to be explicit about where the money goes.

Many diners order the famous rotisserie chicken dish at Zuni Cafe.

Santiago Mejia/The Chronicle

“I didn’t want to lump the cost of paying employees a good salary with the cost of salmon,” Pilgram said.

The restaurant is far from the first to try a tip-free model. The discord within Zuni is not unique either. Restaurants without tips often meet resistance from veteran servers, who are used to earning more. That’s part of why San Francisco’s Bar Agricole reinstated tipping in 2016.

Zuni has retained fewer servers than cooks during the pandemic, though it’s hard to say whether that’s due to the overcharge or other factors, such as people leaving the industry or moving out of the area, Norris said. While nine of the 20 cooks who worked there before the pandemic remain, only three of the 23 servers stayed, according to Norris.

Although waiters’ salaries are lower, they now receive additional benefits such as paid health insurance premiums and paid time off. Norris isn’t sure if Zuni’s model means fewer servers are requesting work there. The restaurant is fully staffed, Norris said, though the new servers tend to be less experienced than usual.

Zuni’s light-filled dining room, where plates of glistening oysters and small mountains of shoestring fries have graced the tables since 1979, feels like a second home to many. Before Wade was employed by Zuni, he was a loyal customer for 40 years. Eating there, he said, has always felt special, inclusive and exceptional.

Wade wants to be a part of what feels like a major “social experiment” at an iconic restaurant. But he feels conflicted.

“They’re asking the servers to give and give and give the tips they would have received,” he said, “but they don’t get much in return.”

Elena Kadvany (she) is a staff writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @ekadvany

Source: www.sfchronicle.com