0:37

0:37

Intro. [Recording date: January 5, 2023.]

Russ Roberts: Today is January 5th, 2023 and my guest is poet and lawyer, Dwayne Betts. He is the creator of the Freedom Reads Project, an initiative to install curated micro-libraries of 500 books in prisons across the country, a project we spoke about on his first appearance. This is his third appearance on EconTalk. Dwayne was last here in May of 2022 discussing Ralph Ellison and Primo Levi.

I want to encourage listeners to go to econtalk.org where you’ll find a link to our survey of your favorite episodes of last year.

Dwayne, welcome back to EconTalk.

Dwayne Betts: I know it’s always a pleasure to be here. I’m chasing Mike Munger.

Russ Roberts: You’re close. Well, with this third episode, you’re on your way. I lose track. I think Mike is in his 40s, but just a few more dozen. Couple dozen. Well, three dozen. Well, more than that.

But I would never underestimate you, Dwayne. All things are possible.

1:38

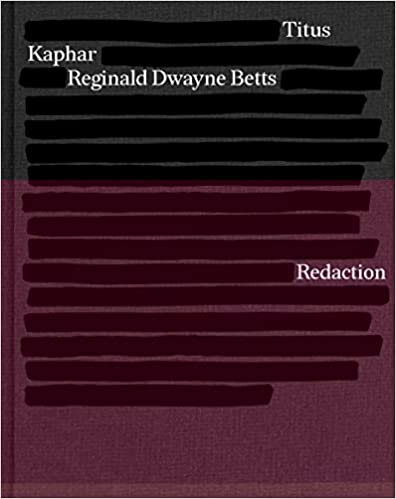

Russ Roberts: So, we have three topics today. If we get to them. We’ll see. We’re going to talk about beauty in prison, which to many would be an oxymoron. We’re going to talk about what’s happening with your library project. And then we’re going to talk about your latest book, which is quite unusual in many dimensions. That book is Redaction, is the name of it.

Let’s start with beauty. [More to come, 2:00]

Now, you recently wrote about beauty in prison in a piece in The New York Times. It opens this way”

The first morning I woke up in a cell I was 16 years old and had braces and colorful bands covering my teeth. My voice cracked when I spoke. I was 5-foot-5 and barely weighed more than a sack of potatoes. Before my 18th birthday I’d scuffle in prison cells, be counseled to stab a man (I declined) and get tossed into solitary confinement five times. And still, of those years, the memory that endures is the moment a prisoner whose name I’ve never known slid Dudley Randall’s “The Black Poets” under my cell door in the hole.

For listeners who didn’t hear your first appearance, and of course we’ll link to it, how’d you get to prison at 16 and how did that book that was slid under your door by a stranger who you’ve never known now and never met–how’d it change your life?

Dwayne Betts: One of the things I find challenging is, as you know, as you get older, some of the excuses you make for your younger self start to wane just because, like, all of a sudden you’re in contact with people who you think could be you. Right? It’s almost like you meet yourself constantly. When I was 20, that wasn’t the case because when I would meet a 16-year-old, they felt like me. Even when I was 25 and when I was 30. But, now that I’m 42 and I got a 15-year-old, that question–how did you end up in prison at 16?–is one that I find baffling. Because I realize that the answers that I thought made sense no longer make sense.

But, the short of it is that I carjacked somebody. And, it was December 7th, 1996. And then the next day we got arrested driving. Well, actually we got arrested at a mall. We were shopping with a credit card that didn’t belong to us. That’s the short answer, is that I carjacked somebody. I got caught.

One of the funny things that people don’t realize–they think that you’re just wild and you’re running the streets. The first thing I did was confess. And, it wasn’t the pressure of having police pointing pistols at me. I think it was that I was living in a place where I expected to go to college, wanted to go to college, but it was just much easier to engage in the violence that was around me than to avoid it. And, it was much easier to imagine that I could have a foothold in that world, even if just momentary, than to recognize that that thing would change the way I saw myself and the way others saw me for the rest of my life.

And so, I confessed immediately. Didn’t even know how much time I would get. I just confessed so that they would drop some of the charges. And, I stood in front of a judge, 16 years old, facing life in prison because carjacking carries life in Virginia. And, I remember sitting in my chair and my family got up–a couple people in my family, a couple family friends. They explained how I carjacked the man because I didn’t have a father. And, my mom, she didn’t get up and testify on my behalf, but she was in the room. And, I just remember thinking, ‘Man, nobody told me that not having a father doomed me from the jump.’ And so, when the judge asked me what I wanted to say, I remember saying I apologized to the victim and I apologized to my mom and to my family. And, all I know is I didn’t do it because I didn’t have a father.

But the wild thing–and this is what I’ve really gotten no further to truly being able to answer–is I didn’t provide the judge what reason why I did it. I just knew what wasn’t the rationale.

And anyway, I went to prison. And, it’s so interesting because it’s the most humbling thing in my life. I thought I was so much better than so many people, my peers, because I was getting good grades without trying. I thought they were on a path to perdition. I ended up in prison before all of them. And, it’s something that’s really humbling when you get into a place like that and you recognize that this is your community. And you got to figure out, man–you know, if you hate them, you hate yourself. And so, with some tortures[?], I think about being a 16-year old-in this God forsaken place and trying to find meaning. And, that’s why the books became so invaluable. But, yeah, that’s how it happened.

Russ Roberts: That book sliding along the floor that went under your cell door, how long had you been there before that happened? Do you remember?

Dwayne Betts: Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, definitely. That’s one of those things that is unforgettable in the sense that, like, I had been reading books all of the time. We all have origin stories and I have different origin stories, too. I should say, like, one of the first ones was I got locked up when I was 16 in my 11th-grade year. When I was in the 10th grade, my history teacher caught me reading in the classroom. And, I was reading Sherlock Holmes. I had it under my desk. And, he came back and busted me. And, I thought he would take my book and yell. And, he just said something to the effect of, ‘That’s a good book.’ And so, what happens is I walk up to him afterwards and he’s reading a philosophy book and he lets me borrow it. And, I remember being deeply, deeply enthralled in this work of philosophy. He’s asking these questions like how do you know exist? And, I was captured by it. And, he let me borrow it.

And, he did two things. One, he introduced me to this book called Sophie’s World. And, it was this 1500-word book. It was this young girl who ended up meeting all the great philosophers. And, it was an intro-to-philosophy book. But, I hadn’t[?] got my hands on it. And, the second thing he did was he was trying to organize a trip to the Holocaust Museum for the whole class, but the school wouldn’t permit it. So, then he told us, ‘If you want to come in the summer, if you meet me there I can get you a private tour.’ Now this is five months before I go to prison. Before I carjacked a man. Before I get nine years in prison. That summer I go to the Holocaust Museum with this teacher. And, it’s my first experience really with understanding what the Holocaust is. But, even thinking about what it means to be Jewish as an idea, as a notion, right?

So, I get locked up and I’m trying to find a way back. And, I got this teacher that’s telling me I can help you get your high school diploma. And, essentially what my course of study became with her was: look, you have enough credits to graduate right now. All you need to do is finish 11th grade and take 12th grade English. So, I did all of my classes at the county jail and then she gave me 12th grade English. And, what 12th grade English consisted of is reading everything. I’m reading King Arthur, I’m reading Ernest Gaines, I’m reading anything that I want to read and anything that she tells me to read. And, she says, ‘What do you want to read?’ And, I said, ‘I want to read this book Sophie’s World.’ I think about this teacher and I said, ‘I want to read Sophie’s World.’

And so, she’s like, ‘Okay, I’m going to get you Sophie’s World.’ And, she comes back a week later and she says, ‘I think you’re mistaken. Because I was looking for it and I can’t find a book called Sophie’s World. I think you want to read Sophie’s Choice.’

Russ Roberts: Not the same book.

Dwayne Betts: And, you know, I’m 16, and it’s like, ‘Woe is me.’ And, then I read Sophie’s Choice and my world is blown. And, I go from Sophie’s Choice to The Confessions of Nat Turner. And so, in my own head I tell this origin story about becoming a poet, but I think the reality is even before I had became a poet, something else had to happen, which is I had to get exposed to literature that let me have some sensitivity to understanding that it’s not just woe is me.

So, this is 1996. It’s 1998 when I ended up–so I read Sophie’s World, I read Sophie’s Choice in 1996. It’s 1998 when I’m at the first prison that I’m at. I’ve been sentenced, I’ve been transferred downstate to the prison. And, something happened on the yard and I ended up getting put in solitary confinement.

And, it was the summer of 1998. Books were contraband, so they took all of my books and they didn’t let anybody really have books back then. But, you would hear guys on the door asking for books. And, then people would slide them books. And it was just like an underground library. If somebody had a book and you asked for one, they would give it to you. And, they wouldn’t ask you what you wanted. So, I read so many Reader’s Digest books. But I remember, I was like, ‘Yo, somebody send me a book.’

And, then this poetry book, Dudley Randall’s The Black Poets, slides under my cell.

But, the truth is, though–at first, I was, like, ‘What am I going to do with this?’ Read poetry? You know, I’m 16, 17 years old, I’m in solitary confinement. What is a poem going to do for me? But, I discovered Robert Hayden, Claude Mckay, Lucille Clifton, Sonia Sanchez. Like, so many fascinating writers.

But, the thing that really turned me into a poet was I discovered Etheridge Knight. And, he had this poem in there called “For Freckle-Faced Gerald.” And, one of the lines was, “Sixteen years hadn’t done a good job on my voice.”

And, I’m a kid when I’m reading it. And it said [Note: lines not in original order but otherwise accurate quote–Econlib Ed.]:

With his precise speech and innocent grin,

he couldn’t quite win

the trust and fists of the black cats around him.

And, it’s this poem about this 16-year-old kid who ends up getting raped in prison.

And, the poem was written in the 1970s.

And so, I was thinking, like, ‘Woe is me.’ You know, I’m 16, 17 years old, I’m in prison. And, it’s a whole cohort of us. And, I’m thinking this is the first time this has ever happened in the world. I can’t believe this is going on.

And, then I read this poem that’s about somebody who could have been me in the 1970s. And, I just thought, ‘Wow. A poem could be history. It could be psychology.’

And also, I read it and it made me grateful for the life that I had. Which is: You can be grateful for anything in prison, but I didn’t really have precise speech, I didn’t have an innocent grin; and people loved me even in prison. And, even in the hole I knew. And, I was not a tough guy. I was in the hole. I was probably the hole because somebody swung on me and didn’t really retaliate. So, it’s not like I was a tough guy.

But, I read that poem and I knew the thing that the poet did was capture a story that the person who experienced it couldn’t because the person who experienced it might not have survived. And, at that moment I was, like: ‘This is the thing I want to be. This is the thing I want to do.’

And, it’s really strange to commit to doing something or being something when you’re so young. But, you know, I did. And, all these years later–I committed to being two things, actually. I committed to being a criminal, too, not understanding the decision I was making, and then to being able to commit to being something else and have the other thing last longer than the first thing is still something that’s pretty humbling to me.

13:27

Russ Roberts: It’s amazing. So, in this piece for The Times, unintentionally or not in what you just said, trying to make a life. You’re in prison but you still make a life. I think those of us who have not had to deal with that kind of thing just have a very flat, stereotyped view of what it means to be in that situation. Not just in prison, but being convicted of a crime and having an identity suddenly thrust on you or chosen by you that is an unbearable surprise.

And yet, there’s other stuff going on there. It’s not as flat as it looks. You write later in that piece, talking about prison at Rikers Island,

The conversations about places like Rikers are usually limited to the violence that takes place there, as if prison, like the streets we walk each day, isn’t filled mostly with people attempting to get by. People who reach for beauty in every way they can. During my time in prison, I got into a single real fight. People don’t understand how many of us sought to become more than our crimes or how many of us starved for lack of a conduit to the dignity that we sought.

So, what does that mean when you reflect on your own experience and then on your experience of going back into prisons recently with books? And, we’ll talk about that in more detail. But, what does it mean to reach for beauty? Can you appreciate that when you’re there?

Dwayne Betts: One thing that’s really interesting, actually, is one of my friends criticized my first book, and he said, ‘Yeah, I read it. I read it in a couple days.’ And, he said, ‘But, what got me is: this ain’t Oz [the TV show–Econlib Ed.].’ And, he was like, ‘Prison ain’t just Oz.’ Now I read my first book–I mean I wrote it. And, I tried really hard not to make the book Oz. Right? But, a good friend of mine who had been sentenced to life in prison, his critique was: You didn’t capture the substance of everything else that’s going on here and–

Russ Roberts: Oz, meaning just a horrific hellhole.

Dwayne Betts: Oh yeah. Oz, meaning the–it’s these certain narratives about prison that persist and Oz was the television show that was about life in the jail. And, I’m sure Oz contained more in it than just the horror; but what people know from Oz is the horror.

And so, the question for him was, as a writer, how complex do you make this portrait? And, every decision you make is a choice. And, I don’t think in the first book I wrote about what it means to reach for beauty. But, I do think it exists in prison, and it exists in a lot of ways. You see a bunch of grown men playing–they didn’t really let us play football in Virginia. But, around Thanksgiving–I remember this one Thanksgiving, snow on the ground–and they let us play football. And, you see a bunch of grown men running around playing football, and of all ages–I mean, that’s something that’s joyful and it’s people trying to recapture their youth. You see people playing basketball.

But, you see people actually–like, I remember walking into a prison and my cell partner was 56 years old and I was in my 20s. So, that means that now he’s probably in his 80s. But, he was crying at a table and there was a circle of men around him. And, I just thought something’s gone profoundly wrong for this guy who has been locked up for 25 years to be crying in public. And, he had made parole. And, nobody made parole during that time. And, he was crying and his friends were around him.

And so, I think that it’s complicated, because to say something like, ‘Is there beauty in prison?’ is, like we started this conversation with, in a way it’s like a oxymoron. But, there is sometimes beauty.

I remember the first dude that defended me. He was this El Salvadorian guy with tattoos all over his body. And, he used to draw roses on an envelope with an ink pen and get this astonishing depth of detail and shading just by using an ink pen.

So, I do think there’s beauty in prison. You don’t want to, like, trivialize the experience and act like it’s just this one thing, but in trying to really engage the world to say how horrific it is, it’s very easy to forget that there are these moments of beauty. And, it’s easy to forget that in all of the language and the work around criminal justice reform, the thing that people don’t really do a lot is we’ll say: What does it mean to actually fundamentally and radically change the lived experience of people inside? To say, like: ‘That’s the thing I’m doing.’ I might not get you out of prison. I might not shorten your sentence. I’m not even advocating for criminal justice reform in my current work. What I’m saying is that you need another iota of beauty in your life and the vehicle for that literally can be a book. Because I think the other moments of beauty I had–it’s like when somebody slid that book under my cell. It’s these conversations around literature I had.

I mean, I remember a guy calling me once. I’m doing a reading in upstate New York, and I was like, ‘Oh, I’m going to answer this because this is my friend calling me from prison,’ and I try to answer anytime somebody calls me. Which is the most disrespectful thing you could do ever to an audience. And, I’m like, ‘Oh, look man, I’m doing this poetry.’ I’m like, ‘You know what, you want to listen in?’

And, I put him on speaker so that he could hear me. And he hears the audience laughing. Somebody in the audience says hi to him. And, like–I think that’s a moment of beauty. That’s a moment of richness. That’s an opportunity to be more connected to the world.

And so, I do think there’s beauty in prison. I think that it’s not enough. And, I think that we should push. Because if we push to make it more, I think we remind ourselves of who we are and we give ourselves the opportunity to revisit the idea of who we want to be instead of being stuck in the circumstances, so to speak.

20:08

Russ Roberts: I don’t want to trivialize the challenge of being a prisoner, but of course all of us have this challenge of remembering that there’s beauty in the world. Very easy to go through life just missing it. It is everywhere. You just have to pay attention, and paying attention is really hard. I don’t know why it’s so hard. It shouldn’t be. There’s some places that are physically more aesthetic than others. There are some places that offer more glimpses of the transcendent and the awesome than others. But, almost every place has beauty in it in some fashion. I think that the–what you said reminds me of Emily Dickinson. I think I have this right: ‘My heart stirred for a bird.’ The idea that I yearn to see something magical, beautiful, transcendent, awe-filled. I don’t know. It’s an under-experienced part of the human experience and I think it’s just because we don’t pay enough attention.

Dwayne Betts: Yeah. I remember once–I had a bit of a charmed life in some ways–but everybody has. And, it’s that thing about paying attention. I was just trying to teach my son this notion of paying attention.

But, like, even the phrase ‘to pay attention’: like, what is the sort of–that vehicle that you have to give the world? What is the money that you have to give the world? And, it’s just your attention. And so, what does it mean to pay attention to something? And it’s remarkably so much of a choice.

And I remember, I was in this cell at a juvenile detention center before they sent me to the adult jail and later to prison. I would sneak a book into my cell at night and read it. And, I got all caught up in, like, the Jonathan Livingston Seagull books. And so, I had them in my cell and then aunt would send me some, and she sent me one of her books. And, the guard, he walked past and he saw me reading and he chastised me. He just worked the night shift. But, then when he opened the door to take my book, he saw what I was reading; and I guess he had read similar books and he was into the books and so now I had a friend. He let me keep the book and then I would read and I will fall asleep when I read, and so he would wake me up before shift changed and get the book from me and put it back so that I wouldn’t get in trouble.

And, I remember once he gave me the book that I had in my locker and I’m reading it and I turn the page–I get to the middle–and I swear, a dozen four-leafed clovers fell out of the book. ‘Cause my aunt, she had taught me how to find four-leafed clovers. I search four-leafed clovers until this day when I’m walking and I find them pretty consistently. But, she would find them and put them in books, and I do the same thing.

But, I open this book and, like, a dozen four-leafed clovers fall out. And, what that reminds me of is the searching for a four-leafed clover is a decision for her to pay attention.

And, then putting it in a book and storing in a book and then later to give the book to me. And, it was all happenstance. She probably had no clue that those four-leafed clovers were in that book because she had that book 10 years, 15 years before she gave it to me.

And so, anyway, I do think that what you do is you wait for moments like that.

And, you get to choose what moments you imagine are remarkable. I think a lot of times we forget that we get to choose. And it might be–some people might think the four-leafed clovers are trivial. I know, because they looked at me sometimes when I’m on the corner sitting down and walking my dog and I look and I find a four-leafed clover. They’d be like, ‘What are you doing?’ I’m like, ‘Well, we looking for a four-leafed clover.’ But, for others, it’s a moment of beauty and it captures something that matters. You know?

Russ Roberts: Yeah. You’re also looking for your aunt, which is pretty beautiful that you can find her on a street corner in Connecticut somewhere.

24:11

Russ Roberts: That’s pretty sweet. So, the literal sense in which you are trying to bring beauty into prisons with the Freedom Reads Project. So, when I think of it, here at Shalem College, we do a–it’s a little like what your project is. Not quite the same. But, there’s a trail, like the Appalachian Trail, here in Israel. It’s called Shvil Yisra’el: it’s the Israel Trail. And, you can go from the full north and south of the country on this trail. And, Shalem College, I’m president of–before I got here–I love this decision. I had nothing to do with it, but I love it–we put out boxes of books on the trail. Scattered it along the trail. And, you can go there and pick up a book.

It’s often a book that–maybe always; I don’t remember–but, that we’ve published in our press. And, I’m sure people are walking along and thinking, ‘What’s that box?’ And, they go and look at it, and they go like, ‘Oh my gosh. It’s got books in it. That’s amazing.’

And, you’re bringing books into a different kind of wilderness, different kind of desert, different kind of trail. But, the part I wanted to emphasize is that you made a decision to make the bookcases that house those books beautiful. You didn’t just say, ‘Well, we’ll put a bookcase in a library and it’ll have two book cases that’ll hold 500 books.’ You designed–somebody designed–a gorgeous, curved, wooden bookcase. We’ll put links to the project online of course to this episode. You can go look at it yourself, listeners. But, they’re beautiful. They’re really beautiful.

They’re not practical for me because they’re not flush to the wall because they’re curved. But they’re perfect for prison. So, talk about that decision and why you did that.

Dwayne Betts: Yeah. It really was iterative. Basically, somebody said to me, ‘What would you do in this world if you could have a bigger impact and it wasn’t about money?’ And I thought, ‘Well, we put millions of people in prison. I would put a million books in prison.’

And, I thought about the books. I thought about the prison is like a glass and the people are like water. And, I thought of the books like ice cubes. And, if you add enough ice cubes to a glass of water, the water overflows. And I thought that if you add enough books to prison that we might conceptualize what we do to each other. On both ends, too. It’s on both ends of the spectrum. I think people in prison understand harm and violence as much as anybody else. It’s not to just to say that the world is unjust. It’s to say that the world is unjust in really profound and complicated ways. And, in some ways what we do with prisons is allow ourselves to ignore the injustice.

And, I just thought the idea of books and bringing more and more books into prison would profoundly alter the way we saw the space and the way people inside saw the space. I thought a lot of things would happen.

And so, I was like, ‘Okay, well how will you do this? Will you just do a bookshelf?’ And, I was thinking it was going to be a 500-book collection. Sir Walter Raleigh had 500 books when he was at the Tower of London. And, I thought, like, 500 books is a sufficient number of books to, like,–especially if they’re great books. If they have weight to them. If it’s a sufficient number of books to carry you through a stretch of time.

Now, I also thought–I’m pretty well read, but I have huge gaps just based on not having the opportunity to read some books when I had the time. And, I thought prison is a lot of time. And, I also thought that books fundamentally are just so much better at changing people’s minds and the way they see the world than arguments.

And so, it was like: What kind of books? And, it was mostly fiction and poetry. And some philosophy and some non-fiction; but mostly fiction and poetry. Because I think a novel–for me, like, reading Sophie’s Choice made me much better understand what it meant to carry the experience of the Holocaust around than reading some nonfiction would have. I think reading–we could all go down the list.

But then the question was, ‘Okay, so you’re going to put the books in, how will you?’ And, at first I was going to do a bookshelf. Like, a case that’s on the wall, your wall behind you. And then I thought, ‘Well, but that’s taking them so much space. People in prison, they’re doing pushups on the wall so the wall is valuable space. They’re leaning against the wall to talk.’

And then, the thing is, if you go to your bookshelf, you exist at your bookshelf and it’s you communing with the books. Right? It’s not a community that gets built from that experience. Maybe one person stands beside you but y’all are shoulder to shoulder, y’all are not looking at each other in the face. And, again, it’s just like two people that get to take up all of that space.

So I thought, ‘Okay, I don’t want it up against the wall.’ So, then I decided not to have it up against the wall. I had to deal with prison. I had to deal with blind spots–the Prison Rape Elimination Act and the fact that you can’t obscure sight lines.

And so, that led me to think: Okay, well now it has to be 44 inches high. And I thought–I’m working with MASS Design at the time, the architecture and design firm that built Bryan Stevenson’s memorial, that’s built hospitals around the world and doing one of these silent gardens at Galluadet. They do some interesting things.

And, I was working with this guy named Jeffrey, this architect there. And, we settled on, like, 44 inches high and thinking to make it curved. Riffing on Martin Luther King’s, ‘the arc of the universe bends towards justice.’

But the thing is, by doing it that way, one, we could maximize the number of books we could get in a small space because we could make the books accessible on two sides. But also, by making it curved–the typical library has three bookshelves and around three bookshelves that’s curved, 44 inches high, six to seven people could just browse at one time. And, what happens is when you’re looking at those books, you’re not just looking at the books, you’re looking at the person across from you. And, it literally creates a space.

And, then the question was: Well, what would the material be? And I got really obsessed with material. I was, like, ‘We’re going to make it out of wood. We’re going to make it out of hardwood. We’re going to use maple and walnut and oak and cherry.’ And, the reason was because the wood lasts forever, and it’s beautiful. When you go into a prison it’s just straight lines and right angles and it’s just, like, steel and concrete and plastics. Right?

And so, I was, like, ‘We’re going to use a wood.’ Every time I see one I put my hand on it and I touch it because it’s life that’s coming out of it. And, a lot of people argued with me: they say, ‘Well, why don’t you just get Ikea bookshelves? If you got Ikea bookshelves then you can do this thing.’ And, I was, like, ‘Well, if we got Ikea bookshelves, one, the prison won’t permit the Ikea bookshelf, right?’ Because that’s usually made by veneer and the shelves are really, really thin and they can become weapons. But, two: It’ll miss the depth of beauty. And, it would actually miss the process that goes into the construction.

And so, at this point, the production of one of these is a journey for everybody involved. It’s this transformation of the wood. It’s the labor. The people’s hands who are literally crafting these things that are a beauty.

And, you know, I was thinking about that Biblical story where somebody washes his–I can’t even remember the story because–I know the story, actually. I think it’s a woman is washing Jesus’s feet with her hair or something. I forgot what they said the story meant. What it was supposed to mean. But, what I think about it is just, like: Who is to say who is worthy of a beautiful thing? Who gets to decide that question? And, anybody who is engaged with this project, when you’re working on it, you’re building it, it’s just the most beautiful thing that is in the house of most people that I know. Nobody has something that’s this beautiful.

So, when you work on it, you know that you’re designing something that has the kind of attention to detail, the kind of care, and the kind of cost that exceeds what a lot of us are capable to bringing into our home. And, frankly, none of us will bring this into our home because it is not efficient. And so, you work on this thing and you know that it’s something that’s profoundly beautiful. It forces you to ask, so: Does this person deserve this? And, in every step of the process you say yes and you say they deserve it. Not even because they’ve done something that’s like: this is the most brilliant scholars in prison or these are the most thoughtful human beings. No. They deserve it because it says something about how we want people to be treated and seen in the world.

And so at the end of the day, we have actually seen it transform spaces. And, not to–you know, not to act as if it’s this a truly existential moment for everybody: but it is existential. A sort of transformative experience, I think, of, for a lot of people it creates the opportunity for–you read L. A. Paul’s work, too. I think it does create the opportunity for transformative experiences for so many people that’s involved.

And, we put one in for the staff, as well. And, I think the thing that’s radical about that is–we used to have a saying when the CO [Commanding Officer] is getting on our nerves, it’s like, ‘You’re doing life, too. You’re just doing it eight hours at a time.’ You know: ‘Where your cell phone at?’ You know what I mean? If you want to reach your wife right now, how you going to do it? You come in here with a plastic bag that has to be see-through because they don’t trust you no more than they trust me. And, correctional officers havea higher rate of alcoholism, higher rate of domestic violence, higher rate of stress than people in a lot of professions in this world.

And so, by bringing one in for them, too, it’s just radical. You get to see just a moment. I’ve seen it. Just to get to see a moment that they’re saying, like; Damn, this is a bit of light in a dark place. And, it’s light in a dark place, not just for people that’s doing time; it’s light in a dark place for people that works there. And, the really radical thing if it ever gets to this point is the permissions that it gives you. When you put a library in a housing unit I think it gives permission for the men there to see each other as more than just, you know, criminal, convict, spades player, athlete. But, to see a person in public as a reader. Because you don’t have wide access to the library.

And then if you get to the place where the COs [Correctional Officers] get a chance actually to read, and that’s a part of the ethos and the structure of the day for them, then I think that they get to see themselves as something other than the jailer. You know? And, the people doing time get to see the COs as something else. They get to publicly be seen as a reader. It’s only one CO the whole time I served time that I saw as a reader. He was the guy who worked at the door if you wanted to go to the law library. And, he would have these books every day and they would be on his desk, but he would have them turned over as if it was like illicit material. And, I would be like, ‘What are you reading? Why you don’t want us to know? You must be reading one of them romance novels.’

And I was a GED [General Educational Development] tutor at the time so every time I came in I would mess with him about his books. And, he was kind of a hardass, and people disliked him because he took his job seriously and he would search you and he felt like he was responsible for making sure contraband wasn’t passed back and forth. And so, people disliked him. And, I didn’t care because I wasn’t passing contraband. And, he had these books and so I was just messing with him every single time. And, then I got an opportunity to work in a law library, but he had to approve whoever was going to get hired because it was–he was like, ‘Look, if I don’t approve the person, then they can’t get hired,’ because, I think, that if you work in the law library, you get access to computers so you can make gambling tickets and things like that. And he was like, ‘I just need to trust the person.’

I’m this young kid. Me and him, our whole relationship had just been me messing with him over these books. And, then when I go up for the job, he okays me to get the job. And, I know a lot of it had to do with just this back and forth that we had about me trying to discover what he was reading and him not telling me.

But, I worked in the law library and that’s how I learned how to do legal research. And, I ended up going into law school. And so, years and years later I end up going to Yale Law School. And so, it’s just this way in which I think everything is interconnected and to create this space of beauty creates opportunities that I couldn’t even predict on the front end, but I know will happen on the back end.

37:02

Russ Roberts: So, how many books have you put into prison so far, roughly? How many libraries have you been able to–

Dwayne Betts: So, it’s actually been really radical because we started it out–the first time you and I talked we were part of Yale Law School, and then we separated and now we’re an independent 501(c)(3). [More to come, 37:26]

And, it was an idea. It was, like, all a dream. At this point we’ve done 60 libraries across seven states in 19 prisons. Later this month we’re doing–and I do say it’s an experience and it’s labor, right? When I say that we had these things called freedom ambassadors and the freedom ambassadors are, like: You want to be able to come into a prison and not be a lawyer.

So, for instance, we did 11 libraries at a women’s prison in Connecticut. They got 11 housing units; we put a library on every housing unit. But, that’s 5,000 books and that’s 33 bookshelves. And so, you’re physically picking them up and taking them into a space, and that’s labor. And so, when we’re working with the staff, different relationship. But, if it’s 5,000 books, that means there’s hundreds of boxes and you’re opening boxes and you’re taking the plastic out. And so, when people come inside to support the work, sometimes they are our ambassadors. And, you can’t put books on the shelf without talking to the people around you.

So, a lot of times we end up getting in conversations with staff, we get in conversations with the people inside. We tell them about the project.

But yeah, so at this point we’ve done 60. And, we’re doing 18–it’s a two-day stretch later this month–we’ll do 18 in a men’s prison in California. And, then there’s a women’s prison across the street and we’re doing five there. We’ll come back and do more at that women’s prison. But, over a two-day stretch, we’ll be putting in 23 libraries.

So, yeah, we have gone from this thing being a dream and an idea to actually having states reach out to us and say, ‘How can we make this happen?’ And, it’s the South. We’re going to be in North Dakota in a few months. We’ve been to Colorado. We’ve been to Angola in Louisiana. And, we hired people who just came home. It’s a couple guys who worked with the Freedom Readers, it’s been their first job.

And, one of the most deeply moved things–I did my solo show in Angola at the–they got a rodeo at Angola that they do every year. And so, they got this rodeo space, and I did my solo theater piece there. But, what has been really interesting for me is at Angola, one of our guys, this guy named James Washington, he did 25 years there. Got locked up when he was 15. So, he grew up in Angola. He just came home. We go there; and he built them with his hands. And, he started doing woodworking when he was in prison.

And so, we’ve returned with these beautifully handcrafted walnut shelves. And, I see him interacting with dudes that he’s known for years. And it was deeply, deeply, deeply meaningful and powerful. And, having him there I think just made me recognize that when you talk about that search of beauty and that want for beauty, it is persistent and it’s evident that it brings people joy when you see a circumstance like that. When you see somebody like him bringing them in. You just see this immediate connection. So, yeah, we’re really excited about the work. And, I think we did 50 libraries last year. We’ll do 150 this year.

Russ Roberts: What’s the total? Do you have a goal?

Dwayne Betts: Yeah, we have a goal. The goal is really to saturate prisons. And, I think sometimes we don’t understand–

Russ Roberts: Saturate. Did you say saturate?

Dwayne Betts: Saturate. Because you don’t want to create more inequity. So, people don’t understand why we put them on housing units. We put them on housing units because a lot of prisons do have libraries, but the libraries are open from eight to five. And, if you have a full-time job, then you don’t go to the library. And, if you got a prison with, like, a thousand people and one library, it’s impossible for all of those people to regularly go to the library anyway.

But, more importantly–we’r thinking about this combination of books and beauty and what does it mean to witness somebody being a reader? Because the readers go to the library. But, then even when you go to the library where you get exposed to The Iliad, where you get exposed to The Odyssey, where you randomly pick up–it’s a great book–A Gentleman in Moscow. If you’ve never heard of it, then how do you know about it?

So, by us curating this 500-book collection, I think we basically are curating opportunities. And so, each prison will have, like, between six housing units and 10 housing units. And so, if we say that we want to saturate because we don’t want to create more inequity, then we always try to put libraries on 60% of the housing units, right? So that it could be a thing that people experience and not just some special thing for this group of prisoners who are working in the kitchen or for this group of prisoners who are taking college courses. It could be something that’s democratic and it’s for everybody.

And so, if you just take the number of state prisons, it’s 1500 state prisons. And, you multiply that out, we’re talking about trying to build 10,000 libraries. And so, I do say we have a goal. The moonshot is to make this a part of the lived experience of somebody who does time.

Suffering is a part of the lived experience of somebody who does time. I do think books were my conduit to becoming a different person. Books were a conduit to me understanding myself better and understanding the world better.

And so, we want to make that opportunity present in anybody’s experience of incarceration. And so, yeah: Our moonshot goal is–sometimes I don’t even want to say it out loud because it’s a significant cost. It’s a logistical nightmare. I’ve found myself now really deeply understanding woodworking in a way that I had no idea about it when I started the project. Understand what it means to ship products from, like, Connecticut to Colorado, from Connecticut to California. And, I also understand something about what it means to try to build a labor force. Right?

And so, if I articulate the big goal, it feels a little bit overwhelming. But the big goal is to do five, 10, 15,000 of these libraries because that becomes five, 10, 15,000 opportunities. Not just for people in prison to discover books and beauty, not just for people who work there to discover books and beauty, but for us to make it more porous.

The wall that separates prisoners from those on the outside becomes far more porous with a project like this. And, I think that’s meaningful for all of us. Even if you just have–you hate to use yourself as an example, but, like, two, three, four, five, 20, 30 people get to have some of the experiences that I’ve had in this life–both when I was in prison and since I’ve been home. I think that there’s something of a life well-lived if I could be the vehicle for others to get to experience some of this stuff.

43:47

Russ Roberts: Do you hear from people who are reading the books? Do you know if they’re being read?

Dwayne Betts: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

So, there’s been occasions where we’ve sent books out before they’ve been published. Honorée Jeffers. I think her book won a National Book Award, The Love Songs of W.E.B Du Bois. Her publisher gave us, like, 30 copies and we sent it to a group of guys in a prison in Texas and they read it before it came out and they wrote all these handwritten notes about the book.

And, but, I once did a Zoom with women in a different Texas prison. I once did a Zoom–when we first did the library, one of the first places we put one at, it was a segregated housing unit. Right? And, it was for people who were in protective custody. And, when I started this, I wasn’t even–I was thinking about myself. So, I wasn’t in PC[?]. And, I spent a lot of time in the hole. But I was thinking about myself in general population. And, then in collaborating with the DOC[?], they was like, ‘Well, we need to put one in segregated housing unit. These guys never go to the library.’ They know. And, they live their lives in a cell, you know? Because they’re afraid. And they have legitimate reasons to be afraid a lot of times.

So, they set up a Zoom call with me and these guys. Right?

And, one of the dudes knew my name and he had read my book and he got in a argument with me about why wasn’t my book in the library? And, he’d be like, ‘This all mattered a whole lot more when I realized that you did it, because I’d not[?] read your book’–it was kind of good, too. It was like kind of good.

But, it was this guy, though–I’ll never forget this man–it was this guy. It was an old white dude. It was an AA [Alcoholics Anonymous] meeting and everybody introduced themselves and said how long they had been in prison. And, I also thought that I did[?] the project for the kid that was like me.

But, what I found is the project has ultimately been for the me, who, if I was still in prison. You know, the people that I’ve talked to the most about this work have been people who’ve been locked up for 20 years and 25 years.

And, this guy says, ‘I’ve been locked up for 27 years and I don’t know if you know this, but I’m Italian.’ And, I was like, ‘Wow. Why would I know that?’ And, he said, ‘Man, but I picked up this book, Barskins.’ He’s like, ‘This novel, man, is about a town that’s just the town where my family comes from.’ And, he started telling me how he had been inside for so long that he had forgotten what home was. And, because we had that book in the collection, he was saying that he reconnected with that space.

So, it’s been interesting, man, talking to people about it. And, we have some videos online. We got a newsletter. You can subscribe to the newsletter. We try to produce stories to give you a glimpse of what it means. And it is–it’s always sort of humbling–because people, when you go in and you’re unboxing the books, one of the things you hear is, ‘I wonder if that book is there.’ And, then they’ll find it and be like, ‘Oh man, I ain’t think you was going to have this.’ And, sometimes it’s like, ‘I always wanted to read this.’ And, 500 books, it’s something for everybody to discover that they’d never heard of.

But, I snuck Adam Smith in there. We had talked about this before. I snuck your book on Adam Smith in there. That’s how I snuck Adam Smith in there, through your book, as opposed to the actual Adam Smith book, because it’s really dense. But, I think the thing is: somebody’s going to pick that up. And, I just remember being introduced to the idea of what it means to be lovely. And so, somebody will pick that up and get introduced to the idea and it will literally, I know, carry them through a bunch of days.

So, yeah, we’ve gotten feedback and the feedback has been–I mean, right now it’s been consistently good just because–for better or worse, books are not grenades.

48:08

Russ Roberts: I was preparing for this interview. I just interviewed Tiffany Jenkins. You haven’t heard it yet, Dwayne, because it hadn’t come out yet, but I interviewed her yesterday. It’s about the British Museum and other museums that have stuff from the past that they haven’t returned. Or excuse me, they’re bring pressured to return. Like, the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon and many, many, many other things like it. And, in the course of her book, there’s a little history of museums and the desire to collect. She tells a story in there–I didn’t get to talk about it on air, so I’m cheating a little bit and I’m adding it here–about Hans Sloane, whose collection becomes the British Museum, when he dies. This guy who lived, I think 1660 to 17-something. And, he’s a collector. He’s a crazy collector. He’s got 50,000 books and 17,000 pieces of something. And, he collects everything.

And, for a while–since the British Museum didn’t exist, and he was the collector–his house was the museum. And people would come to his house.

And, the composer, Handel, who wrote, you know, “The Messiah” and other great works of music, supposedly came to his house, put a buttered muffin on top of one of the manuscripts in his collection–which he didn’t like.

And, you know, I’m reading that–I’m–or I’ve heard it from–I read it I guess and then I heard it. Talking to Tiffany. We didn’t get it in the episode. But I’m thinking: I can relate to that, because–I think I’ve told the story before. When I was seven years old, I threw a book. I tossed it across the room and my dad gave me a spanking. And, I never threw a book again. And, I’ve always thought of books as something sacred. As something that you don’t put a buttered muffin on and you don’t throw them. And, when you read them, you don’t crack the spine. And, you treat them with deep, deep respect.

And, as I was thinking about talking to you about this, I’m thinking: Why is it that you and me–and we’re not alone–why do we think of books as so special? As so potentially transformative? It’s part of the reason I’m president of a college that emphasizes actually reading books: that, not just hearing about it in a lecture. Our students are in small seminars, so they actually read the books. Really a novel–pardon the pun–novel idea.

And, sure: books change your life, and they’ve changed mine, obviously.

I don’t think that’s the reason. I think I have, and I suspect you do as well, something close to a religious attitude toward books–that, they represent in many ways the highest form of human achievement. That we can speak and have language is extraordinary. That we can somehow communicate across Connecticut to Jerusalem is extraordinary. [More to come, 51:24]

Source: news.google.com